Ah, the human brain. Even the most normal example of a human being can attest to it’s unreliability and penchant to stop working at the most inopportune moments, but for some of us it’s inability to properly transmit signals and produce chemicals makes our lives even harder than most. Luckily we have handy-dandy neuroscience to help explain why, when we are already late to a lunch meeting, some of our brains decide that tapping EXACTLY 32 times on the doorknob is the most important thing we could be doing (yes, I’ve done that and yes, the people I was meeting were irritated).

While many imaging studies have been done comparing the brains of neurotypical people against those of people with OCD, very little conclusive data have been gathered (because of course not). Luckily, there have been enough consistencies that some theories have been developed. I’ve linked the studies I’m referencing below, if you’d like to read them in their entirety, but I’ve taken what I consider the most pertinent information and condensed it into what I hope is a more decipherable read. In this particular post, I’ll be focusing on the physical size and structure of different areas of the brain, and how that may impact a person’s likelihood of having OCD. I’ll cover chemical imbalances in a later post.

Let’s get sciency.

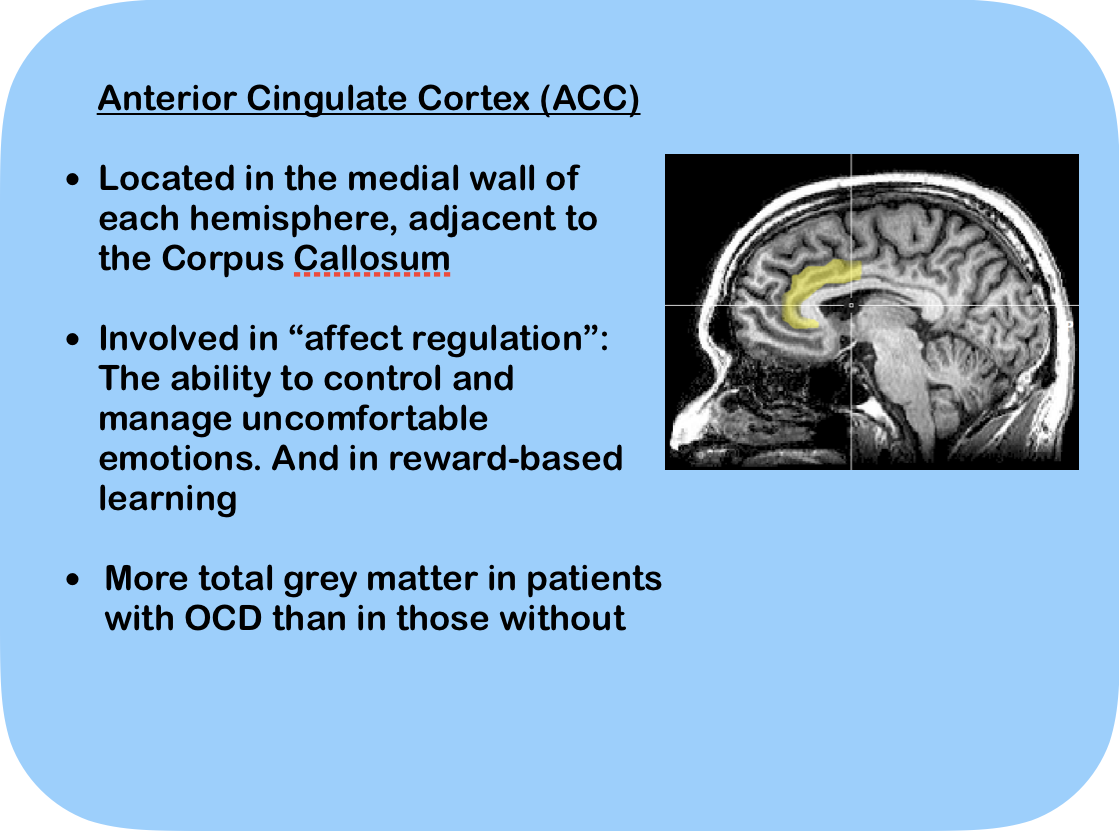

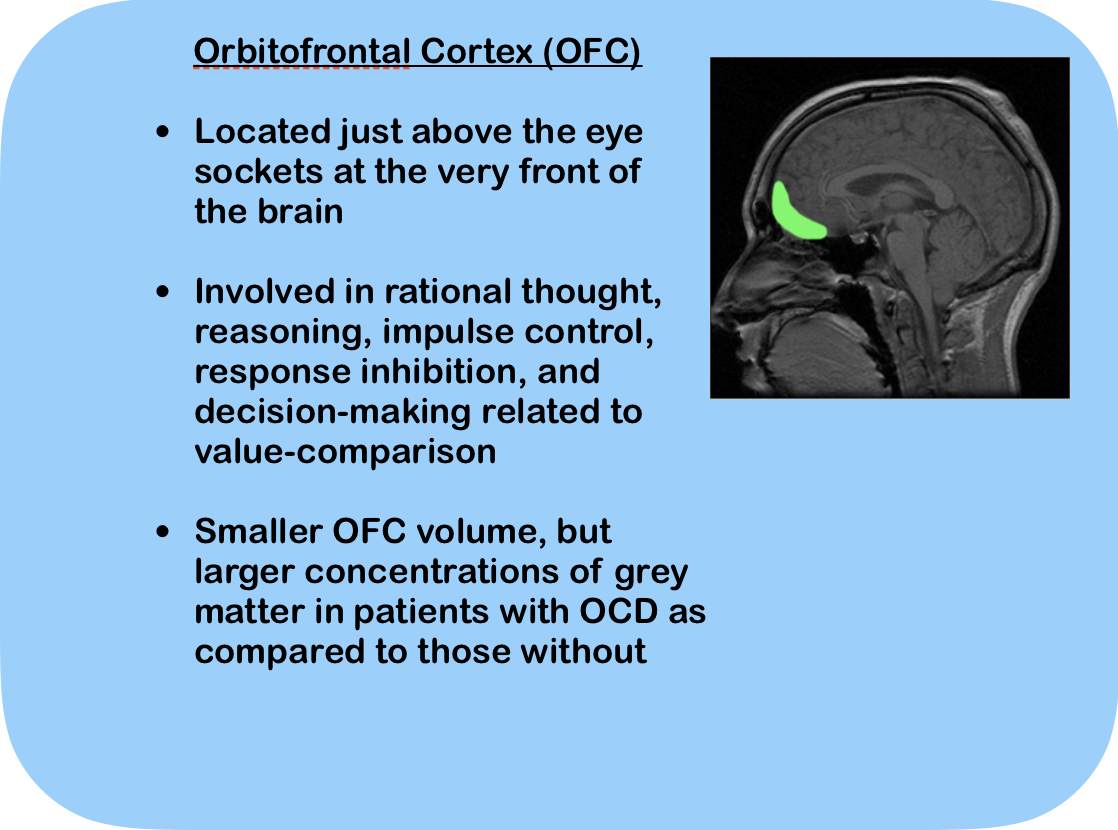

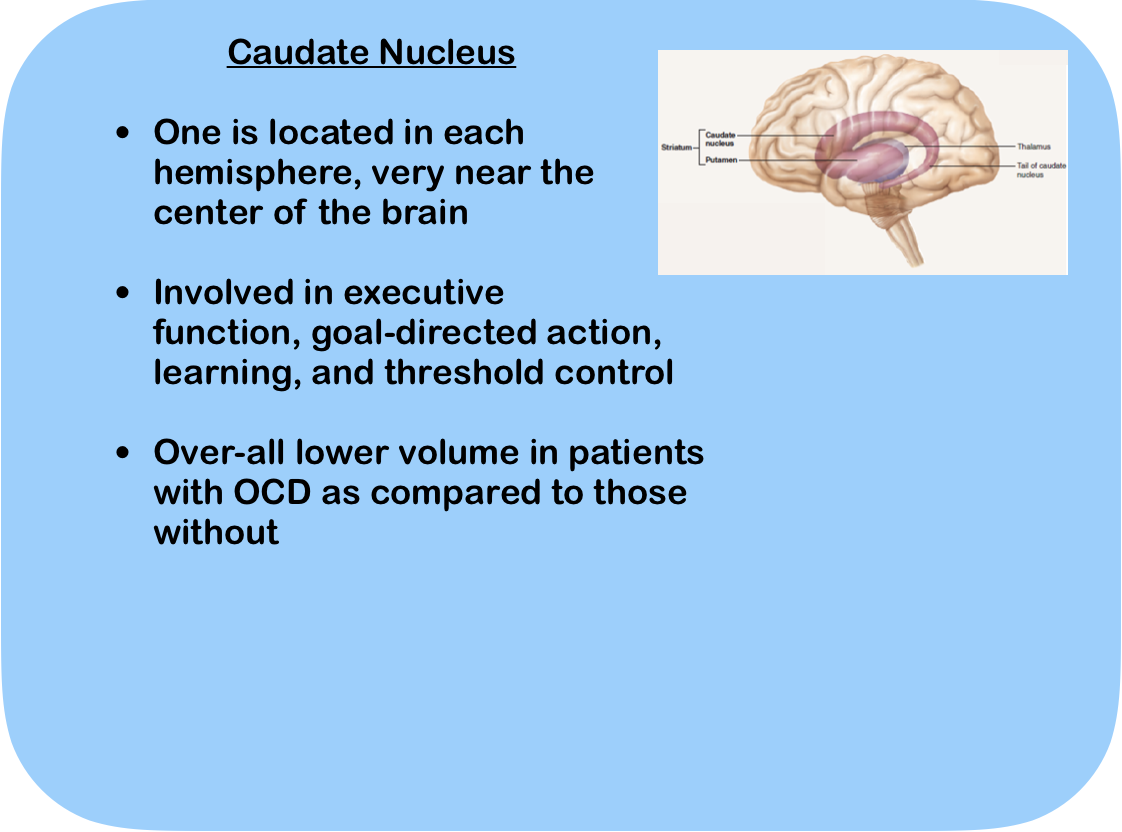

The three areas of the brain that seem to have the most impact when it comes to a person having (or not having) OCD are the Anterior Cingulate Cortex, the Orbitofrontal Cortex, and the Caudare Nucleus. Below are those areas of the brain with a description of it’s location, primary functions, and structural difference between those with OCD and those without.

To begin to understand how these areas and their structures contribute to OCD, we need a little bit more information about grey matter. Grey matter is a part of the central nervous system (CNS) and contains most of the neuronal cell bodies in the CNS. To put it simply, the grey matter is where the “events” of thought, learning, and intelligence occur, and is responsible for memory, emotions, decision making, and self-control (amongst other things, but we have enough to think about as it is).

In the ACC, there is more total grey matter in people with OCD, meaning there are more neuronal cell bodies and more “events” occurring. In an area that is responsible for dealing with uncomfortable emotions, an increased amount of work going on is a strong indicator of OCD, or at least some sort of mental illness. But is this a cause, or an effect? Scientists still aren’t sure, because as we’ve already established, the human brain is complicated and unpredictable (and dumb. But I doubt we’ll get a scientific article on how dumb the human brain is).

Humans have the most developed OFC of any other known organism, but what does it mean when a person’s OFC is smaller than average? While it probably doesn’t mean that we’re devolving into primates, it can theoretically have an impact on how that area of the brain functions (again, there’s never been a definitive conclusion, so much of this information consists of theories and educated guesses. What are scientists even for, anyways?). Despite it’s smaller volume, the OFC also has increased concentrations of grey matter, which implies that there’s still more going on in this area even though there’s less room. In an area of the brain responsible for impulse control, how could these changes affect a person’s thinking and behavior? It is possible that even with more ‘events’ occurring in this area due to increased grey matter, it’s harder for the brain to separate rational thought from irrational and regulate impulses due to it’s smaller-than-average volume? The world may never know.

The Caudate Nucleus is different from the other two areas that we’ve looked at because there’s actually one in each hemisphere of the brain. Most scholarly articles about the Caudate Nuclei describe them as “C” shaped, but I think they look more like tadpoles, or something a little less SFW, but I digress. Overall, the Caudate Nucleus is smaller in people diagnosed with OCD than it is in people without the disorder, implying that there is reduced or limited function. Limited function in the Caudate Nucleus would mean limited goal-directed action, which could be a vital part of the development of OCD.

So what does all this nonsense mean? OCD consists of a complicated mix of impulses, irrational thinking, and decision making. Reward-based learning is involved as well when we consider that people with OCD are rewarded whenever they engage in a compulsion, as their anxiety is temporarily eased. All of these areas of the brain are involved in the feelings and behaviors associated with OCD, and all of these areas have notable differences between those with OCD and those without. And while there may be no definitive conclusions to be drawn from the data that we have, there are certainly some clues as to why our brains work differently. And remember, the human brain is dumb, and I’ve done some postulating and educated guessing in this blog post. So don’t cite me, bro.

Thanks for reading, I’ll be back soon.

Sources:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4476073/

https://neuroscientificallychallenged.com/blog/know-your-brain-orbitofrontal-cortex

https://neuro.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/jnp.23.2.jnp121